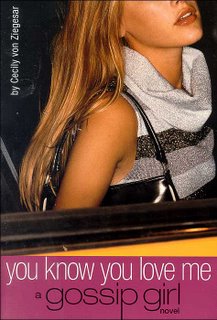

I read the first few pages of the third installment of the Gossip Girl series at the bookstore the other day. These books are the Laguna Beach / Sex in the City of Teen Lit, and they read much like an issue of Teen People or Cosmo Girl, only with less heart. Those who compare the series to Cruel Intentions do so in order to flatter it. Sure, there's intrigue and drugs and bulimia and blow jobs, but there's not really a psychological or moral conflict at it's core. It's a slick and superficial world, and -- I think -- a rather perfect articulation of capitalism.

I've long been wondering about the relationship between gossip and capitalism. I've often felt the recent boon in celebrity gossip correlates to these ne0-conservative / post- September 11 / Bush-era / war times. What is it about the intimate details (both trivial and sordid) of high profile personalities' lives that so captures mainstream America's imagination right now? Everything from crossing a street to giving birth is treated as "news," so long as the subject is "famous" or "important" enough to elicit our interest. And yet even gossip's most ardent devotees are quick to point out that following these stories is simply an "escape." The content is often recycled and even the subjects seem to be not only ephemeral but also disposable. Nothing in this world "sticks" really. Everything seems slippery and half-real.

Juxtapose this with the public outrcy surrounding James Frey's supposedly fictional "memoir" A Million Little Pieces. and the controversy surrounding gender-bending "memoirist" J.T. Leroy. Are people mad because they read something they thought to be true and now feel betrayed to find out it may not be, or are they mad because they spent 22.95 on something that was "falsely advertised" as truth?

When people buy a memoir like Frey's, they are likely looking for titillation, an empathetic connection with the author, and an opportunity to gauge the events of their own life. In such a success oriented culture, the memoir is one of the few places where the difficulty of life is acknowledged. The legitimacy of these tomes seems to be vested in the fact that these are just ordinary people telling their stories. And these stories are considered valuable because they are true.

While there is much about contemporary gossip that seems focused on making the secret familiar, it's relationship to "truth" is commonly acknowledged to be dubious. And the majority of gossip items tend to merely debate a given report's accuracy. Thus the pleasure and excitement of following gossip seems to come mostly from the possibility of truth, but not necessarily the promise of truth.

The tenuous nature of gossip's connection to truth is reflected in it's etymology.

O.E. godsibb "godparent," from God + sibb "relative" (see sibling). Extended in M.E. to "any familiar acquaintance" (1362), especially to woman friends invited to attend a birth, later to "anyone engaging in familiar or idle talk" (1566). Sense extended 1811 to "trifling talk, groundless rumor." The verb meaning "to talk idly about the affairs of others" is from 1627.

The word literally goes from meaning "godparent" to "trifling talk, groundless rumor." The disparity between the meaningful and the trivial is also echoed here. Why, in age of increasing globalization and in a country that seems to be in the midst of carrying out it's grossest, most imperialistic aspirations, is the value of celebrity gossip increasing? And why, in an age of "plausible deniability" -- an age in which politicians and corporate executives appear to be increasingly comfortable with a rather loose definition of "truth," are we so quick to string up this one guy whose life doesn't really affect anybody?

No comments:

Post a Comment